|

Description:

|

|

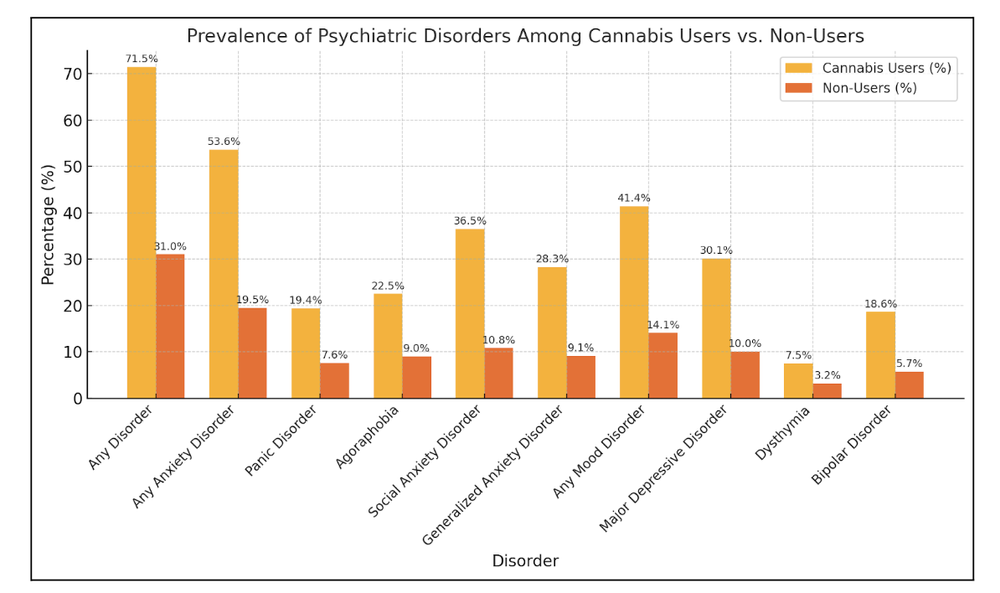

Danielle Liu*, Daniel Cuevas**, Liam Browning, MD; Christopher Campbell, MD; David Puder, MD Corresponding Author: David Puder, MD Reviewers: Erica Vega, Joanie Burns, PMHNP-BC *Danielle Liu is the first author on the sections on depression, anxiety, and PTSD **Daniel Cuevas is the first author on the sections on cognitive function and sleep The authors declare no conflicts of interest and have no financial relationships with any pharmaceutical or cannabis companies. By listening to this episode, you can earn 1.25 Psychiatry CME Credits. Other Places to listen: iTunes, Spotify At a time when cannabis is not only legalized, but marketed as therapeutic, it is essential for healthcare professionals to be well-versed on what the research truly reveals about the reality of cannabis and its effect on psychiatric outcomes. Given the increased accessibility and its widespread popular appeal, it is incredibly common for patients to identify cannabis as one of the few things that alleviate their symptoms of anxiety and depression. However, real-world scenarios highlight the true clinical effect that cannabis has on patients’ mental health journeys, and the importance of this issue. Take the case of the patient whose family members encourage him to continue using cannabis because without it, he becomes a “different person” - far more irritable and anxious and completely unable to function because of his overwhelming emotions. This is not a picture of a patient for whom cannabis is healing, but destructive. Cases like this have been increasingly seen, raising relevant questions about the true effects of cannabis on depression, anxiety, PTSD, and other mental health outcomes. Can cannabis cause depression? Is cannabis effective for anxiety? How does cannabis affect sleep and PTSD symptoms? What are the best ways to identify and treat cannabis use disorder? In this episode, we continue our discussion on the psychiatric risks of cannabis (see episode 240) by examining the latest scientific research on cannabis’s impact on mood disorders, PTSD, sleep, and cannabis use disorder, and discuss important considerations for treating patients with problematic cannabis use. Cannabis And Depression Cannabis use is correlated with increased likelihood of virtually all psychiatric disorders, as illustrated below in Figure 1 (Blanco et al., 2016). This is particularly concerning given the fact that marijuana use is associated with a myriad of deleterious mental health outcomes. When looking at the specific example of cannabis use in individuals with depression, it was found that over 30% of people with depression reported using cannabis in the past 30 days, and more than 15% reported daily use. Moreover, this study highlighted an alarming increase in cannabis use rates in individuals with depression in recent years: From 2005 to 2006, people with depression were 46% more likely to use cannabis and 37% more likely to use it nearly every day. By 2015 to 2016, these odds had increased significantly, with individuals with depression being 130% more likely to use cannabis and 216% more likely to use it daily (Gorfinkel et al., 2020).

Figure 1: Prevalence of psychiatric disorders among cannabis users compared to non-users. This figure highlights the percentage of individuals diagnosed with various psychiatric disorders within the past year, comparing cannabis users and non-users. Disorders include broad categories like "Any Disorder," "Any Anxiety Disorder," and "Any Mood Disorder," as well as specific subtypes such as panic disorder, social anxiety disorder, and bipolar disorder. Data adapted from Cannabis Use and Risk of Psychiatric Disorders Prospective Evidence From a US National Longitudinal Study (Blanco et al., 2016).

Let’s delve into what the research shows us about the relationship between cannabis use and depression.

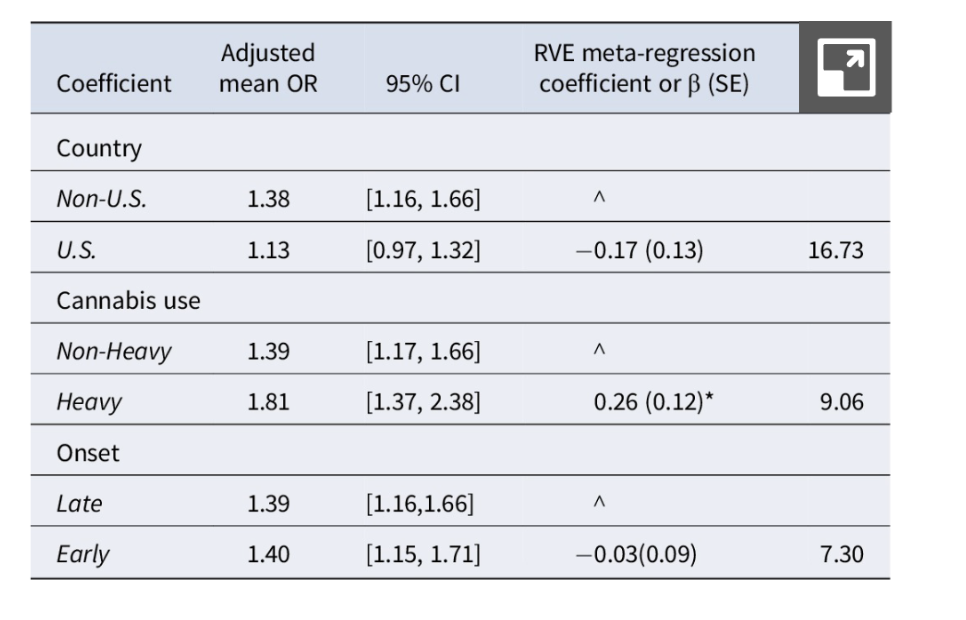

Are depression and CUD associated?People with Depression are more Likely to Have a Cannabis Use Disorder A cross-sectional study done of the survey results from over 16,000 U.S. adults, conducted from 2005-2016 found that those with moderate-to-severe depression (per PHQ-9 scores) had nearly double the odds (OR 1.90 95% CI, [1.62-2.24]) of any past-month cannabis use and over triple the odds of daily/near-daily use (OR 3.16 95% CI [2.23-4.48]), compared to those without depression (Gorfinkel et al., 2020). Interestingly, this association grew stronger from 2005 to 2016, which may suggest that as public perception of cannabis as a “helpful” remedy increased, more depressed individuals turned to it. A meta-analysis published in February 2025 looked at the association between cannabis use (coding for usage prior to the age of 18 and heavy cannabis use, which was defined as “cannabis dependence,” “cannabis use disorder,” “diagnosis of cannabis abuse,” “chronic cannabis use,” “persistent use,” and “daily use”) in any form and self-reported or clinical depression in 22 studies. The analysis used multilevel meta-regression for effect size moderators. Cross-sectional studies and studies that focused on only special populations [including war veterans, LGBTQ-only populations, or participants seeking treatment for a baseline mental health issue] were excluded (to reduce confounding factors). This study showed that compared to people who do not use cannabis, people who use cannabis are more likely to have self-reported or clinical depression (OR 1.29, 95% CI 1.13-1.46) (Churchill et al., 2025).

Note. Reprinted from “The association between cannabis and depression: An updated systematic review and meta-analysis”, by Churchill et al., 2025, Psychological Medicine, 55, e44. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0033291724003143

The association between cannabis use and depressive symptoms was also corroborated by a systematic study from April 2024 which examined 78 studies. Although this study inherently was limited by the heterogeneity of the studies included and the cross-sectional design of a number of the included studies, the review still demonstrates the trend of cannabis use in people with mood disorders and suggests that cannabis use may be associated with poorer prognosis in major depressive disorder (Sorkhou et al., 2024). There is also a 2023 JAMA study that shows that CUD is associated with higher odds of depression (Jefsen et al., 2023). A 2021 meta-analysis of epidemiological surveys representing the United States shows that the prevalence of comorbidity between cannabis use and major depression varies between recreational, medical and heavy cannabis use: the prevalence of comorbidity was 6.9% with cannabis dependence, with an odds ratio of 4.83 (95%CI 2.37 – 2.85); 4.7% with cannabis use disorder, (odds ratio of 2.6, 95%CI 2.37 – 2.85) and only 1% with cannabis abuse (odds ratio 2.37, 95% CI 1.38 – 4.07) (Note: Although cannabis and abuse are now under the same category under the updated DSM V, some of the studies included in this meta-analysis were published before CUD was defined) (Onaemo et al., 2021). However, these studies do not tell us whether cannabis causes depression. RCTs are limited in cannabis research, so we are stuck with mostly observational studies. To understand the relationship between cannabis and depression, we can look at studies meeting the Bradford Hill criteria of dose-response (higher potency, greater frequency of use) and temporality (cannabis use preceding onset of depression) along with controlling for confounds (socioeconomic, adverse childhood experiences, genetic factors). If someone starts smoking cannabis, does it increase their risk of developing depression?Twin Studies Twin studies assessing two different monozygotic twins who are discordant for cannabis use offer unique ways of controlling for genetic and environmental confounds because monozygotic twins share the same genetics and have a more similar environment than other controls. A large retrospective study of 6181 monozygotic and dizygotic twins showed a greater frequency of reported MDD in twins who used cannabis more frequently (>100 times vs. <100 times), with an odds ratio of 1.98 (95% CI [1.11–3.53]) (Agrawal et a.l, 2017). However, when looking at only the 198 discordant monozygotic twins and adjusting for covariates like conduct disorder, early dysphoria or anhedonia, sexual abuse, and alcohol use, the odds ratio fell to 1.68 (95% CI [1.01-2.80]).Given that the confidence interval reflected marginal significance, this may represent a case of p-hacking, given that such an arbitrary number of 100 uses of cannabis was used to result in significance in this study. The Minnesota Twin Study by Schaefer et al., (2021) examined adolescent cannabis use and its long-term psychosocial impact in a sample of over 3,700 twins. This study found that when comparing monozygotic twins, differences in cannabis use were significantly associated with lower educational attainment, mainly through decreased grade point average, decreased academic motivation, increased academic problem behavior, and increased school disciplinary problems. Furthermore, these same outcomes were associated with poorer socioeconomic outcomes later in young adulthood. Interestingly, this study found that adverse psychiatric outcomes (such as MDD, anxiety disorder, antisocial personality disorder, other substance use disorder), as well as poorer performance on a vocabulary task, were each associated with increased cannabis use; however, these associations did not persist when comparing monozygotic twins on their cannabis use. One limitation here is that for the MZ co-twin analyses only a small amount of cognitive tests were performed, and thus may not accurately represent a full cognitive assessment. Important as IQ would be more encompassing and is one of the strongest individual predictors of career performance, academic achievement, and socioeconomic status.

Take-home: Adolescent cannabis use appears to causally undermine academic functioning and later socioeconomic success, but evidence from twin designs indicates that its associations with depression, anxiety, (and perhaps baseline cognitive ability), more-so reflects underlying familial and genetic predispositions rather than a direct neurotoxic effect.

Effects of Cannabis Use in Adolescents and Prospective Studies A 2019 meta-analysis looking specifically at prospective longitudinal studies from inception to January 2017 investigated the association between cannabis use in adolescence (<18) and risk of depression, anxiety, and suicidality. The study found that cannabis use in adolescence is associated with increased risk for depressive disorder in young adulthood, the odds ratio being 1.37 for users compared to non-users (95% CI 1.16-1.62) (Gobbi et al., 2019). However, this study is limited by its high heterogeneity. Further, many of the included studies did not adjust for other drugs of abuse and cigarettes, genetic predisposition, personality disorder, or psychosocial factors (peer drug abuse, school abandonment) which can independently contribute to major depressive disorder. A previous meta-analysis of 14 prospective longitudinal studies controlled for many of these confounds (psychiatric symptoms, socioeconomic status) and also met the Bradford Hill criteria of dose-response and temporality, finding a smaller OR of 1.17 (95% CI 1.05–1.30 for developing depression in users vs. controls; but a greater OR of 1.62 (95% CI 1.21–2.16) in heavy cannabis users (at least weekly use) compared to non-users/light users (Lev-Ran et al., 2014). How could cannabis make depression worse?Another perspective to consider in the relationship between cannabis use and depression is withdrawal-related dysphoria, which can be highly disabling for dependent cannabis users and frequently leads to relapse (in order to alleviate the discomfort of withdrawals). Consequently, once a person is an established, heavy user of cannabis, he might feel down when he is not using, which then “requires” them to use again, reinforcing a cycle where a person needs to keep using cannabis just to feel “okay” and avoid feeling depressed. Is cannabis causing depression, or are people using cannabis to avoid feeling depressed due to withdrawal? Suicide And Suicidal Ideation And Cannabis UseA large retrospective study of 6181 monozygotic twins showed that suicidality in the monozygotic twin who used cannabis more frequently was more likely to be reported (OR 2.47, 95% CI 1.19–5.10) (Agrawal et al., 2017). An integrative analysis of multiple longitudinal studies, comprising between 2500-3700 participants who had been serially assessed between ages 13-30, observed that participants who used cannabis before age 17 daily compared to participants who had never used cannabis had a dose-dependent increase in odds of suicide attempt by age 25-30 (OR: 6.83, CI 2.04-22.90). However, results were confounded by lower educational attainment, more illicit drug use, welfare dependence, depression, etc., so it is difficult to ascertain that cannabis was an dependent predictor of suicide attempt (Silins et al., 2014). A 2019 meta-analysis looking at cannabis use in adolescence and the risk of suicidality found an increased risk of suicidal ideation in users versus non-users (with OR = 1.5, 95% CI 1.11-2.03). The most significant result was that the odds ratio for increased risk of suicide attempts in cannabis users vs. non-users was 3.46 (95% CI 1.53-7.84) (Gobbi et al., 2019). However, this study is limited by its high heterogeneity and an outlier study. A 2017 population-based longitudinal study found a significant difference in thoughts about committing suicide (for non-cannabis users vs. cannabis users without CUD, χ2= 7.54, p=0.0078; for non-cannabis users vs. participants with CUD, χ2= 7.44, p=0.0082), but after adjusting for more baseline confounding factors, this difference did not retain significance, implying that much of the seemingly apparent association between cannabis use and MDD may in fact be associated with sociodemographic and clinical factors instead of cannabis use (Feingold et al., 2017). A longitudinal sample of 6788 adolescents, which followed participants from ages 14-15 to 16-17 and looked at their NLSCY data, found that at least monthly cannabis use at age 14-15 was associated with increased SI (OR 1.74 [1.16, 2.60]) and suicide attempts (OR 1.87 [1.09, 3.22]) two years later in adolescents. In the study, participants had no recent history of depression, and the study controlled for other drug use, life stress, maternal depression, and family dysfunction. This suggests cannabis use’s effect on suicidal ideation may actually be independent of depressive symptoms (Weeks & Colman, 2017). Another study which followed 3134 adolescents aged 11-17 for one year identified marijuana use within the past year (OR = 4.7) and caregiver suicide attempts as the only independent predictors of the first incidence of suicide attempts (Roberts et al., 2010). The major limitation of this study is that no dose-response relationships were investigated. A longitudinal study following New Zealanders born in 1972 and 1973 originally looked at the association between multiple variables and suicidal ideation, focusing on tobacco usage. In this study, only depressed mood, high stress, and low parental attachment at age 15 were significant predictors of suicidal ideation (McGee et al., 2005); cannabis use was not detailed, but this points to how a number of confounders also are independently associated with suicidal ideation as well, which were not accounted for in other studies. Anxiety And Cannabis UseA meta-analysis of 24 longitudinal and prospective studies assessing adolescent cannabis use and later anxiety disorder found increased odds of developing anxiety on follow-up (OR = 1.25; 95% CI, 1.01 to 1.54; I2 = 39%), with a reduction in this OR when the analysis was restricted to studies that used a structured diagnostic interview instead of self-reported questionnaires (OR = 1.15; 95% CI, 1.01 to 1.30) (Xue et al., 2021). Restricting the analysis to high-quality studies, or to studies which considered cannabis use prior to age 18, or to studies published after 1999, resulted in a loss of statistical significance. In general, the ORs are not very impressive, suggesting that there is at best weak evidence that cannabis increases risk for anxiety disorders. Given that the association did not retain significance when cannabis use prior to age 18 was accounted for, it is unlikely that early cannabis use is a significant causative factor in the development of anxiety disorders later in life. If someone starts smoking cannabis, does it increase their risk of developing anxiety disorders?Another 2020 literature review of prospective studies acknowledges a robust positive association between cannabis use and anxiety symptoms and disorders, but points out that minimal research has been suggestive of any causative or predictive relationship in either direction, noting that any evidence supporting a directional relationship (for the most part) does not (for the most part) appropriately adjust for covariates and confounding factors (Garey et al., 2020). One prospective epidemiological analysis of past-year weekly cannabis use did predict panic disorder with agoraphobia (but not without) after adjusting for comorbid psychiatric disorders and sociodemographic factors (OR 1.56, CI 1.11-2.19) (Cougle et al., 2015), and another study noted that daily or almost daily cannabis use marginally predicted the onset of SAD (OR 4.62, CI 2.29-9.31 in unadjusted analysis; OR 2.88, CI 1.4-5.77 after adjusting for sociodemographic variables; OR 2.24, CI 1.12-4.48 after additionally adjusting for alcohol and substance use disorders; OR 1.06, CI 0.99-3.94 after additionally adjusting for comorbid psychiatric disorders) (Feingold et al., 2016), but aside from these studies, such predictive relationships with robust studies have been sparse in the literature. Directional relationship between anxiety and cannabis use

A more recent longitudinal cohort study published in 2022 demonstrated that in the overall study population and in men, increased cannabis use predicted greater increases in anxiety at a later time point. In contrast, more severe anxiety symptoms were associated with decreasing cannabis use. In females, when prior levels of trait-like anxiety predicted increased anxiety symptoms, cannabis use was found to decrease among women who recently experienced worsening anxiety (Davis et al., 2022). Cannabis To Treat Depression And AnxietyCannabis for Depression On the flip side, some have argued that cannabis can be used to actually treat depression. One observational study used data from Strainprint, a medical cannabis app that users input their depression, anxiety, and stress symptoms and tracked their symptoms over time. Twenty minutes after cannabis use, the patients reported alleviation in their symptoms of depression, but longer-term improvements were not found, emphasizing the argument against using cannabis to treat depression (Cuttler et al., 2018). A single-blind randomized clinical trial study in Massachusetts found that getting a medical marijuana card led to increased cannabis use and higher rates of cannabis use disorder symptoms, without significant improvement in pain or depression after 12 weeks. Depression was measured via the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (21 points total), and the study compared scores for people who immediately received access to a medical marijuana card versus those who received it 12 weeks later. Scores were recorded at the beginning of the study, week 2, week 4, and week 12, and the mean difference in the depression score was only -0.5 (p=0.3) (Gilman et al, 2022). Because cannabis can cause patients to feel that their symptoms are improving initially without long-term benefit, using cannabis may in fact play a role in preventing people from getting better. Cannabis for Anxiety Anxiety is one of the most common reasons cited by medical marijuana patients for their cannabis use. The study, which used the medical cannabis app to track usage and symptom response, found a significant reduction in the ratings of anxiety (MBefore = 5.98, SE = 0.12 vs. MAfter = 2.50, SE = 0.14), Wald χ2 (1, 769) = 659.50, p < .001), with reported reduction in anxiety in 93.5% of tracked sessions. Anxiety was exacerbated in 2.1% of sessions, and there was no change in anxiety symptoms for 4.4% of sessions. This difference was observed in both men (Wald χ2 (1, 407) = 244.61 and women (Wald χ2 (1, 362) = 582.32, p < .001), with women perceiving a greater reduction in anxiety (Wald χ2 (1, 362) = 10.78, p < .001) (Cuttler et al., 2018). The randomized clinical trial in Massachusetts found no significant difference in anxiety symptoms after treatment with medical marijuana after 12 weeks. Anxiety was measured via the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale like depression was, and the mean difference for anxiety was only -0.1, (p=0.9). Of course, there was individual variability, and some participants found benefit from the drug, but overall, there was no significant improvement found. Further research is needed to be done in order to direct future medical uses of marijuana (Gilman et al., 2022). PTSD And Cannabis UseAlthough medical marijuana is approved to treat PTSD in some states, the VA/DoD Clinical Practice Guideline for PTSD (2023) recommended against the use of cannabis for the treatment of PTSD due to lack of evidence for its efficacy. Nevertheless, many patients report that cannabis helps with their symptoms or improves their overall life and functioning. We have heard patients state: It helps them sleep because it reduces nightmares. It has helped them avoid their previous addictions, such as alcohol or opioids. It helps them look at themselves from a different perspective, not as negative and more in a positive light. When they come off of it their symptoms are worse, they have more nightmares and are more “on edge.”

An excellent article on the U.S. Department of Veteran Affairs website written by Melanie Hill and colleagues in 2024(a) discusses the use of cannabis in patients with PTSD. They report that cannabis has not been found to improve PTSD symptoms, stating that in “a recent systematic review of 14 studies evaluating the evidence on the clinical effects of cannabis on PTSD symptoms, results did not support the use of cannabis for improving overall PTSD symptoms [(Rodas et al., 2024)].” However, “there has only been 1 RCT comparing whole plant cannabis and placebo for treating PTSD [(Bonn-Miller et al., 2021)]”: “This trial included 2 phases. The first phase compared effects of 3 active cannabis preparations (high THC, high CBD, balanced THC+CBD) and placebo [lowTHC/low CBD marijuana] on PTSD symptoms in 80 U.S. military veterans.” Participants were allowed to self-administer ad libitum up to 1.8g, and there were no differences in grams used throughout the study. Although this was a double blind study, there was a 60% break-blind rate in the placebo group, 58% in the CBD group, and 100% in the high THC group.

After 3 weeks, all treatment groups showed improvement in PTSD symptoms and that there was “no significant difference in PTSD symptom reduction [CAPS-5] between placebo and any of the active cannabis preparations.” After a two-week washout period, “74 veterans were re-randomized to receive 1 of 3 active cannabis preparations [High THC, High CBD, and THC+CBD]. Results showed a significant reduction in PTSD symptoms [PCL-5] in the THC+CBD group only; however, because there was no placebo group in this phase, it is not possible to draw conclusions about the efficacy of cannabis to treat PTSD from these results.”

It may be the case that cannabis reduces PTSD symptoms while the patient is intoxicated, as they cite a study in which 404 medical cannabis users with self-reported PTSD tracked their PTSD symptoms with an app and experienced “short-term symptom relief when using cannabis but no long-term changes in PTSD symptoms” over 31 months (LaFrance et al., 2020). This raises the question of whether cannabis use impacts the effectiveness of therapy: Evidence suggests that a diagnosis of CUD predicts less symptom change during residential PTSD treatment (Bonn-Miller et al., 2013) and continuing or starting to use cannabis after PTSD treatment has been linked to increased PTSD symptoms (Wilkinson et al., 2015). However, other studies have found no association between baseline cannabis use and post-treatment PTSD symptoms (Bedard-Gilligan et al., 2018; Ruglass et al., 2017). In a meta-analysis of 4 RCTs comparing trauma-focused and non-trauma-focused treatments for co-occurring PTSD and SUD, both cannabis users and non-users experienced clinically significant improvements in PTSD symptoms. Additionally, trauma-focused treatments were more effective than non-trauma-focused treatments, regardless of whether individuals used cannabis (Hill et al., 2024b). It is possible that functional problems related to cannabis use, rather than a neurobiological effect of cannabis, might impact PTSD treatment effectiveness. Individuals using cannabis may also have more difficulties engaging in treatment; one study found that baseline cannabis use predicted a doubled risk of dropout from both cognitive-behavioral and pharmacological treatments for PTSD, as well as poor adherence to trauma-focused psychotherapy (Bedard-Gilligan et al., 2018). From these data, the authors conclude that “individuals with comorbid PTSD and SUD do not need to wait for a period of abstinence before addressing their PTSD. A growing number of studies demonstrate that these patients can tolerate trauma-focused treatment and that these treatments do not worsen substance use outcomes.” Cannabis And SleepPatients commonly report subjective improvements in sleep with cannabis, and individuals with PTSD are especially likely to use it in an effort to reduce nightmares. Observational evidence suggests that cannabis can shorten sleep latency, increase slow-wave sleep, and decrease REM latency and duration. This suppression of REM may explain why vivid dreams are a hallmark of cannabis withdrawal. However, these effects may not persist due to tolerance. Over time, the impact of cannabis on sleep often becomes neutral, and in some cases may worsen sleep quality. Evidence in this area is still limited and inconsistent. To date, only 10 randomized controlled trials (RCTs) have directly examined cannabis and sleep outcomes (Amaral et al., 2023). These trials, which investigated different formulations of THC and CBD but not whole-plant cannabis, were short in duration (≤2 weeks) and had small sample sizes. Their findings were generally neutral to slightly positive. A broader scoping review of 50 studies published up to 2023 (Amaral et al., 2023) found highly variable results: 21% reported improved sleep, 48% reported worse sleep, 14% reported mixed outcomes, and 17% found no effect. Taken together, the evidence suggests cannabis may provide short-term, subjective improvements, but tolerance, withdrawal effects, and inconsistent findings across studies highlight the need for further research. Can Adding CBD or Terpenes to Cannabis Decrease Anxiety from THC? The “Entourage Effect” CBD supplementation is common for people seeking ways to reduce symptoms of anxiety. Despite its popularity, there have only been a handful of small studies. One double-blind, placebo-controlled study evaluated the effect of the administration of 300 mg CBD daily for 4 weeks to 17 Japanese teenagers on social anxiety, using the scores of the Fear of Negative Evaluation questionnaire and the Liebowitz Social Anxiety Scale as outcome measures. The mean FNE score decreased from 24.4 to 19.1 after the CBD administration, compared to a decrease of 23.5 to 23.3 in the placebo group, with 2x2 ANOVA resulting in an F of 10.35 (p = 0.003) in the intervention group compared to the placebo group (F = 2.69, p=0.11) (Masataka, 2019). This suggests that CBD may have anxiolytic effects, although the power of this study was weak. Another randomized placebo-controlled study assessing the effect of 300 mg of CBD on anxiety (assessed via Visual Analog Mood Scale score) in participants with PTSD, as they listened to digital audio playback of their report of the triggering event, found that CBD significantly lessened the anxiety among the nonsexual trauma group (mean difference of 8.21, p = 0.008, CI -13.94 to -2.47), although this relationship was not found for sexual trauma (Bolsoni et al., 2022). However, as concluded in a literature review exploring CBD and anxiety, evidence is mixed and limited (Lichenstein, 2022). Notably, there are some ideas about CBD or terpenes resulting in different subjective effects (for example, altering the euphoric state or reducing anxiety) when compared to THC in isolation. The entourage effect theory posits that the non-THC components within whole-flower cannabis influence the overall effects of cannabis. Some believe that other phytochemicals and plant compounds may work synergistically to result in various effects which are different from that of any single compound. Initial studies showed CBD could offset some of the negative intoxicating effects of high dose THC, like anxiety/paranoia: Karniol and colleagues (1974) examined the effects of oral CBD by itself and on THC-induced effects. Although oral CBD (15, 30, and 60 mg) did not reduce anxiety on its own, it did reduce oral THC (30 mg) induced anxiety when given simultaneously. This was replicated by Zuardi and colleagues (1982) using a combination of oral CBD (1.0 mg/kg) and oral THC (0.5 mg/kg). Solowij et al., 2019 (vaporized THC+ vaporized CBD), low-dose CBD potentiated the intoxicating effects of THC, high-dose CBD decreased intoxication, no effect on acute anxiety or psychosis.

However, more recent trials observed no effect on acute anxiety: And a recent trial published in JAMA (Zamarripa et al., 2024) suggested oral THC + high-dose oral CBD (20 mg THC + 640 mg CBD) increased plasma THC and hydroxy-THC concentrations, increased paranoia, and anxiety relative to THC alone (20mg). However, all participants in this study were also taking a CYP-inhibiting cocktail, as the original intention of the study was to observe how these drugs interact with CBD and THC metabolism, not to answer the question of how CBD affects THC. Nevertheless, oral THC relies more on first-pass metabolism than smoking/vaped THC, and produces more hydroxy-THC (active metabolite that’s stronger than THC). So, inhibiting the breakdown of THC and hydroxy-THC with a CYP-inhibiting cocktail and then adding CBD on top of that is likely going to prolong the availability of the psychoactive metabolite.

Of note, orally-dosed CBD has very poor bioavailability (Millar et al., 2018), and clinical doses of pharmaceutical grade CBD given for seizure disorders are 1000’s of mg (von Wrede et al., 2021), which dwarfs the amount used in supplements (5-20mg). For CBD to exert a biological effect, it may need to be taken at high doses, inhaled via smoke or vape, or taken as full-spectrum oil. Furthermore, the safety of vaping CBD-oil is in question, as it may produce toxic byproducts (Bhat et al., 2023; Love et al., 2024). What are Terpenes?Terpenes are a class of aromatic phytochemicals that give the plant its aroma and flavor. For example, limonene is found in lemons and citrus fruits, pinene is in pine needles, and myrcene is in hops. Terpenes are increasingly being artificially added to cannabis, with companies advertising them to lead to different “medicinal” effects, claiming some combinations of terpenes may be more calming while others may give an energized or focused effect, and that users should experiment with different terpene ratios and find what works for them. For instance:

This is questionable, as expectancy effects play a large role in how someone feels when they use a drug. We were only able to find one RCT addressing this: A 2024 double-blind within-subject crossover study of 38 participants (10 males and 10 females of whom completed the study and were included in the data analysis) evaluated the effect of vaporized and inhaled THC alone (15 or 30 mg), d-limonene alone (1 or 5 mg), these compounds together, or placebo on the anxiogenic effects of THC in cannabis. The protocol also implemented an optional 10th test of 30 mg THC combined with 15 mg of d-limonene. The most promising results were observed with the 30 mg THC and 15 mg d-limonene combination, with significantly lower subjective ratings of the “paranoid” and “anxious / nervous” Drug Effect Questionnaire items compared to 30 mg THC alone (p’s < 0.05) (Spindle et al., 2024). This suggests that D-limonene may play a role in attenuating THC’s anxiogenic effects. In vitro binding studies have suggested that the attenuative effects of d-limonene do not directly modulate the effect of THC on the CB1 or CB2 receptors, but rather may act independent from CB receptors. Cannabis, Cognition, And IQAnother important consideration with regards to cannabis use in adolescents and young adults is its effect on cognition and intelligence.

A review and meta-analysis of the literature (69 studies) on cannabis usage and cognition in this demographic (Scott et al., 2018) came to the conclusion that THC can have statistically significant but clinically negligible effects on cognitive functioning for those who used cannabis frequently. However, these deficits seem to diminish given that periods of abstinence longer than 72 hours led to a decrease in effect as well as a loss in statistical significance. Thus, those who used cannabis but were abstinent had outcomes that were not measurably different from those who didn’t use cannabis.

Just like with the literature on cannabis’ effect on other aspects of mental health, there is not a consensus on the exact effects of cannabis on cognition and intelligence.

There was a prospective cohort study with 1,037 members of the Dunedin Cohort followed from birth (1972/1973) to the age 38 (Meier et al., 2012) that sought to test the association between persistent cannabis use and neuropsychological decline, as well as to determine whether decline is concentrated among cannabis users who started using in adolescence. Participants were evaluated regarding cannabis use through interviews at ages 18, 21, 26, 32, and 38 to assess for past-year cannabis dependence based on the criteria from the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM). Due to the fact that there were some members within the study who used cannabis on a regular basis but never met full criteria for a diagnosis of cannabis dependence, the researchers repeated analyses using persistent regular cannabis use as the exposure variable. Persistence of cannabis dependence was defined as the total number of study waves, out of five, at which a study member met criteria for cannabis dependence. Persistent cannabis use was associated with decline broadly across domains of neuropsychological functioning, even when controlling for years of education.

They found that impairment was particularly concentrated among adolescent-onset cannabis users, and more persistent use was associated with greater decline. Those who used cannabis persistently showed greater decline in IQ, and this is reflected in the fact that those who were diagnosed with cannabis dependence at one, two, or three or more waves within the study experienced IQ declines of −0.11, −0.17, and −0.38 SD units, respectively; for context, an IQ decline of −0.38 SD units corresponds to a loss of ∼6 IQ points. IQ decline was particularly pronounced in those who initiated cannabis use during adolescence, with adolescent-onset persistent cannabis usage (3+ diagnoses) was about −0.55 SD (~8 IQ points), which is significantly greater compared to adult-onset cannabis users (p = 0.02). Adolescent-onset persistent cannabis users showed significant IQ decline whether they used cannabis infrequently or frequently at age 38 (decline observed regardless of cessation, p = 0.03 for infrequent, p = 0.0002 for frequent use), whereas adult-onset persistent cannabis users did not show significant IQ decline with cessation (p = 0.73 for infrequent users, p = 0.11 for frequent users), suggesting possible recovery or less vulnerability.

Note. Reprinted from “Persistent cannabis users show neuropsychological decline from childhood to midlife”, by Meier et al., 2012, Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 109(40), E2657–E2664.

Additionally, study members with more persistent cannabis dependence generally showed greater neuropsychological impairment across different areas of mental function. For example, informants reported observing more attention and memory problems among those with more persistent cannabis dependence to a statistically significant degree. Furthermore, the linear effect of persistent cannabis dependence on change in full-scale IQ was significant before controlling for years of education (t = −4.45, P < 0.0001) and after controlling for years of education (t = −3.41, P = 0.0007). IQ decline could not be explained by other factors, even when controlling for hard-drug or alcohol dependence.

Note. Reprinted from “Persistent cannabis users show neuropsychological decline from childhood to midlife”, by Meier et al., 2012, Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 109(40), E2657–E2664.

Note. Reprinted from “Persistent cannabis users show neuropsychological decline from childhood to midlife”, by Meier et al., 2012, Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 109(40), E2657–E2664.

These findings are consistent with the hypothesis that cannabis use may have neurotoxic effects, especially in adolescence when the brain is undergoing crucial development. A limitation to this study was that it could not assess the concentration of THC being used. With regards to the Bradford Hill criteria, there seems to be a dose-response relationship in that more persistent use was associated with greater decline. Notably, the ABCD study, an ongoing prospective study following 11,875 youth from ages 9-10 onward, also assessed cognitive function in a subsample (∼1,200 participants). A recent study of this subsample (Wade et al., 2024) found that compared to controls matched on socioeconomic status (parental education and household income), those with self-reported cannabis use or with positive metabolites in hair had slightly poorer episodic memory assessed via the Picture Memory task (F(1,238) = 4.67, partial η2 = 0.02, p = .03) compared to controls. Several years prior, these groups did not differ on their task performance. There were no significant differences in performance on other tasks related to verbal memory, working memory, attention inhibition, speed, and reading. Cannabis Addiction: Cannabis Use Disorder, Withdrawal, And TreatmentHow Addictive is Weed?There is a popular belief that cannabis is not addictive; however, the evidence demonstrates this is not the case, as 8-19% of individuals who use cannabis have CUD (Hasin, 2018). For comparison, about 15% of alcohol users develop an AUD (Grant et al., 2015). And although more people use alcohol and have a use disorder with alcohol, there are now more people who use cannabis daily, showing that it may be particularly rewarding for a subpopulation of cannabis users. THC’s rewarding effects are attributable to a reduction of GABAergic inhibition of VTA dopaminergic neurons (disinhibition). Some studies have even shown there are genetic predispositions that cause people with schizophrenia and their healthy relatives to release more dopamine and glutamate in the striatum in response to THC (Colizzi et al., 2020; Kuepper et al., 2013).

Cannabis Use Disorder Diagnosis, Treatments And Withdrawal Assessing a Patient for Cannabis Use DisorderWhen assessing a patient for CUD, clinicians can use the DSM–5, which defines cannabis use disorder as the presence of clinically significant impairment or distress for 12 months, manifested by at least two of 11 criteria for a diagnosis of mild CUD, 4-5 symptoms for moderate CUD, and 6+ for severe CUD (Patel & Marwaha, 2024): Taking cannabis in larger amounts or over a longer period than intended. Persistent desire or unsuccessful efforts to cut down or control cannabis use. Spending a great deal of time obtaining, using, or recovering from cannabis. Craving or a strong desire to use cannabis. Recurrent cannabis use resulting in failure to fulfill major role obligations at work, school, or home. Continued cannabis use despite having persistent or recurrent social or interpersonal problems caused or exacerbated by cannabis. Giving up or reducing important social, occupational, or recreation

|

More

More

Religion & Spirituality

Religion & Spirituality Education

Education Arts and Design

Arts and Design Health

Health Fashion & Beauty

Fashion & Beauty Government & Organizations

Government & Organizations Kids & family

Kids & family Music

Music News & Politics

News & Politics Science & Medicine

Science & Medicine Society & Culture

Society & Culture Sports & Recreation

Sports & Recreation TV & Film

TV & Film Technology

Technology Philosophy

Philosophy Storytelling

Storytelling Horror and Paranomal

Horror and Paranomal True Crime

True Crime Leisure

Leisure Travel

Travel Fiction

Fiction Crypto

Crypto Marketing

Marketing History

History

.png)

Comedy

Comedy Arts

Arts Games & Hobbies

Games & Hobbies Business

Business Motivation

Motivation