|

Description:

|

|

Audio Episode Host: David Puder, MD Audio Episode Guest: Nicholas Fabiano MD, Brendon Stubbs PhD

Article Authors: Nicholas Fabiano MD, Liam Browning BA, Christopher Campbell, David Puder MD

Article Reviewers: Erica Vega, MD, Joanie Burns DNP

Corresponding author: David Puder, MD Psychiatry CME for listening to this activity: 1.75 Other Places to listen: iTunes, Spotify Date Published: 12/20/2024

Conflicts of interest: Brendon Stubbs is on the editorial board of Ageing Research Reviews, Mental Health and Physical Activity, The Journal of Evidence-Based Medicine, and The Brazilian Journal of Psychiatry. Brendon has received honorarium from a co-edited book on exercise and mental illness (Elsevier), and unrelated advisory work from ASICS, in addition to honorarium and stock options at FitXR LTD.

Dr. David Puder and Dr. Nicholas Fabiano have no conflict of interests to report.

Introduction On Exercise For DepressionExercise benefits both mental and physical health. Specifically, it has demonstrated antidepressant effects, which are often compared to other first-line treatment options such as medications or therapy. In previous episodes, we have explored various aspects of exercise, including exercise as a prescription for depression/anxiety/stress (episode 010), performance enhancement (episode 012), strength training for depression (episode 018), the best exercise program for depression (episode 096), exercise as a drug for mental health and longevity (episode 142), exercise for the brain (episode 165), and the exercise & mental health 2023 update (episode 179).

In today’s episode, we are delighted to welcome two leading experts in exercise and mental health: Nicholas Fabiano, MD and Brendon Stubbs, PhD. Dr. Fabiano is a psychiatry resident at the University of Ottawa and has contributed extensively to research on exercise and mental health, as well as other innovative topics in psychiatry and medicine. Dr Stubbs is recognized as one of the world’s foremost researchers in mental health and neuroscience, ranked among the top 0.1% of researchers in the field. He has authored more than 2,500 studies, influenced global health policies through organizations such as the World Health Organization and the World Psychiatric Association, and influenced various public health campaigns. Dr. Stubbs has been an instrumental force in bringing credibility and legitimacy to the use of exercise as a valuable treatment modality. Together, Dr. Stubbs and Dr. Fabiano bring unparalleled expertise to today’s conversation on exercise and depression.

We hope you enjoy this engaging episode and encourage you to explore the work of Dr. Fabiano and Dr. Stubbs, as well as our previous episodes on exercise and mental health, for further insights into this transformative area of research. Why Exercise: The Science Behind Its Power To Combat DepressionPhysical activity (PA) is any movement that uses energy, while exercise is a planned and structured form of PA aimed at improving fitness. PA provides many benefits for mental health. It reduces stress, improves sleep, boosts mood, enhances self-esteem, and has specific antidepressant effects (Wegner et al., 2014). Upon contraction, muscles release myokines (cytokines and peptides) that mediate communication with other organs to increase brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) (Oudbier et al., 2022). Studies have demonstrated that PA promotes neuroplasticity through this upregulation of BDNF, which is important for mood regulation (Wegner et al., 2014). There exists also a bidirectional relationship with depression—PA reduces depressive symptoms, while inactivity is associated with increased depression risk (Huang et al., 2020). Given its broad impact on mental and physical health, PA has been included in treatment guidelines for depression as a first-line therapy (Lam et al., 2024).

Public Perception Of Exercise As A Treatment For Depression (Fabiano et al., 2024)Decades ago, exercise was not a serious treatment option for depression. However, over the last 30 years, the sheer volume of research publications on physical activity, mental health, and well-being has become immense. A recent bibliometric analysis of the literature found 55,353 documents on exercise and mental health published between 1988-2021 (Sabe et al., 2022). In particular, a large-scale umbrella review (including 97 reviews [1039 trials and 128,119 participants]) found that exercise was highly beneficial for improving symptoms of depression, anxiety and distress across a wide range of adult populations, including the general population, people with diagnosed mental health disorders and people with chronic disease (Singh et al., 2023b). Although these findings are certainly valuable, the media misconstrued the evidence stating that, “[E]xercise is around 1.5 times more effective than either medication or cognitive behaviour therapy” (Singh et al., 2023a); this misleading headline has since been widely disseminated to millions across news outlets, podcasts, videos, and blogs. This claim erroneously arose through the comparison of effect sizes from “very low quality” previous systematic reviews of physical activity interventions for mental health (Singh et al., 2023b). Given the overlapping 95% confidence intervals and substantially methodologically superior systematic reviews the authors used as a comparison, they made a more accurate statement that exercise is “comparable to or slightly greater” (in mild symptoms).

It is imperative that robust science is communicated widely, but this needs to be done in the interest of science and, in this case, patients. As the media is known to play a crucial role in influencing people’s perception and behaviors, it is imperative that dissemination of scientific information is both clear and accurate. Previous research has demonstrated that subtle misinformation in news headlines, such as the claim that exercise is more effective than medication or therapy, can affect readers’ memory, inferential reasoning, and behavioral intentions (Ecker et al., 2014). Further, readers struggle to update their memory in order to correct initial misconceptions, which highlights the importance of factual messaging to the general public (Ecker et al., 2014).

This is particularly important when it is considered that there is already significant stigma surrounding the use of psychotropic medications, such as antidepressants (Sansone & Sansone, 2012). Thus, wide dissemination of the non-evidence-based claim that exercise is 1.5 times better than other first-line treatments may lead to direct harm to vulnerable patients who may delay seeking specialist support, stop taking medications, or stop attending therapy due to such headlines. Prior evidence has demonstrated that a greater delay to treatment of a depressive episode is associated with a reduced response, and may precede development of a treatment-resistant depression (Corey-Lisle et al., 2004). Further, for those already taking an antidepressant medication, abrupt discontinuation, without physician supervision, can lead to withdrawal effects characterised by dizziness, weakness, nausea, headaches, and insomnia, among others. Moreover, media claims often fail to mention that the evidence for exercise in depression lies mostly in the mild to moderate cases, therefore those with severe depression may be experiencing extreme distress warranting immediate medical attention (i.e., due to active suicidal ideation or malnutrition due to severely reduced intake). What Does The Evidence Actually Show About Exercise And Depression?Meta-analysis of Exercise for Depression (Heissel et al., 2023)

The objective of this meta-analysis was to estimate the efficacy of exercise on depressive symptoms compared with non-active control groups and to determine the moderating effects of exercise on depression and the presence of publication bias. Randomized controlled trials (RCTs) including participants aged 18 years or older with a diagnosis of major depressive disorder or those with depressive symptoms determined by validated screening measures scoring above the threshold value, investigating the effects of an exercise intervention (aerobic and/or resistance exercise) compared with a non-exercising control group were included. The authors found: 41 studies (2264 participants) were included. Twenty-one studies assessed depressive symptoms, while MDD was diagnosed in 20 studies. Percentage of females ranged from 26% to 100%, mean age from 18.8 to 87.9 years. Only non-active controls “such as usual-care, wait-list control conditions or placebo pills” were included. “Studies with any other exercise intervention (such as stretching or low-dose exercise) as a comparator were excluded.” Taking out the low-dose exercise or stretching exercises from this meta-analysis is interesting because these types of studies control for the antidepressant effect of starting an intervention or group activity, allowing for a more accurate assessment of the true effects of exercise. Using studies that compare exercise to waitlist control and non-interventional groups might inflate the effect size of exercise.

Large effects were found in: All exercise interventions (standardized mean difference (SMD)=−0.946, 95% CI −1.18 to −0.71) Individuals with major depressive disorder (SMD=−0.998, 95% CI −1.39 to −0.61, k=20) Supervised exercise interventions (SMD=−1.026, 95% CI −1.28 to −0.77, k=40)

Moderate effects were found in: Based on exercise type:

Meta-regression: Shorter trials associated with larger effects (β=0.032, 95% CI 0.01 to 0.09, p=0.032, R²=0.06). In this study they used unstandardized beta, meaning the average number of standard deviations that the dependent variable changed for each unit change (as opposed to each standard deviation change) on the independent variable. In this example, since the unit of the independent variable is in weeks: if a study lasts 10 weeks, compared to 5 weeks, the effect size might be 0.16 units smaller (0.032 × 5 weeks).

Higher antidepressant use by the control group was associated with smaller effects (β=−0.013, 95% CI −0.02 to −0.01, p=0.012, R²=0.28).

Mean change and number needed to treat (NNT): Mean change of −4.70 points (95% CI −6.25 to −3.15, p<0.001, n=685) on the HAM-D and for the BDI of −6.49 points (95% CI −8.55 to −4.42, p<0.001, n=275). NNT was 2.0 (95% CI 1.68 to 2.59) for the main-analysis, and 2.8 (95% CI 1.94 to 5.22) for the low risk of bias studies. For MDD, only the NNT was 1.9 (95% CI 1.49 to 2.99) and 1.6 (95% CI 1.58 to 2.41) in supervision by other professionals/students.

Network Meta-analysis: Comparing Exercise To Pharmacological Interventions For Depression (Recchia et al., 2022)The objective of this network meta-analysis was to assess the comparative effectiveness of exercise, antidepressants, and their combination for alleviating depressive symptoms in adults with non-severe depression. RCTs that examined the effectiveness of an exercise, antidepressant, or combination intervention against either treatment alone or a control/placebo condition in adults with non-severe depression were included. The authors found: 21 RCTs (2551 participants) were included. No differences in treatment effectiveness among the three main interventions, although all treatments were more beneficial than controls. Exercise vs antidepressants: SMD, −0.12; 95% CI −0.33 to 0.10 Combination versus exercise: SMD, 0.00; 95% CI −0.33 to 0.33 Combination vs antidepressants: SMD, −0.12; 95% CI −0.40 to 0.16 Exercise interventions had higher drop-out rates than antidepressant interventions (RR 1.31; 95% CI 1.09 to 1.57)

Despite the greater drop-out rates in the exercise group, the proportion of participants with adverse events was greater in the antidepressant group, with 22% reporting adverse events compared with 9% in the exercise group.

The authors conclude that the results suggest no difference between exercise and pharmacological interventions in reducing depressive symptoms in adults with non-severe depression.

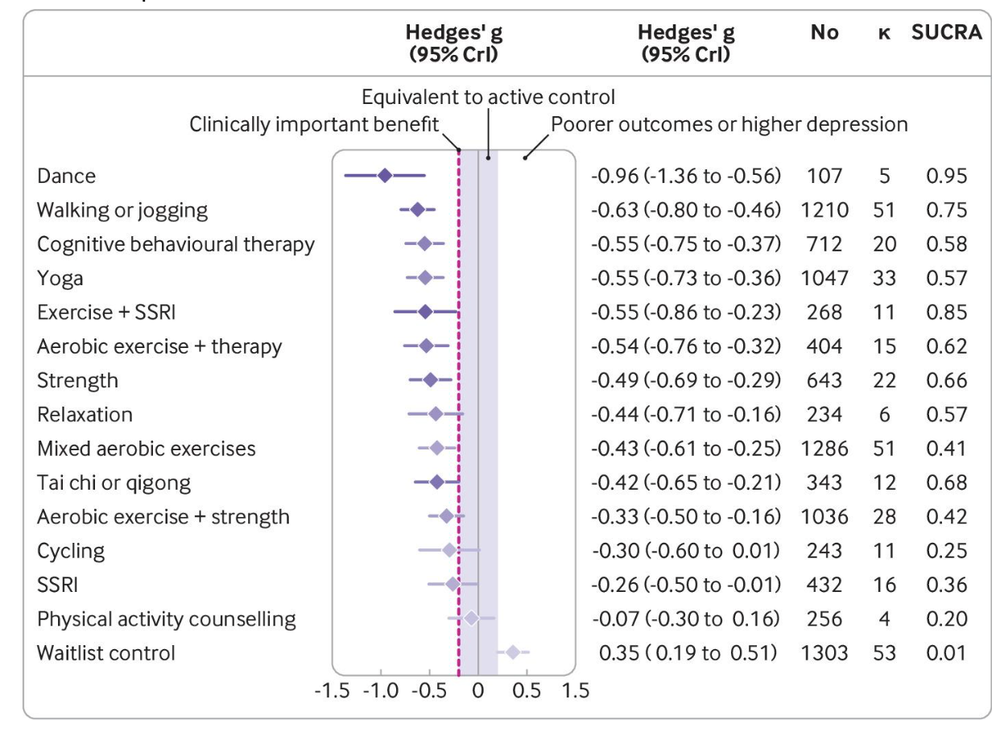

Network Meta-analysis: Optimal Exercise Dose And Modality For Treating Major Depression Compared To Psychotherapy And Antidepressants (Noetel et al., 2024)The objective of this network meta-analysis was to identify the optimal dose and modality of exercise for treating major depressive disorder, compared with psychotherapy, antidepressants, and control conditions. Any randomized trial with exercise arms for participants meeting clinical cut-offs for major depression were included. The authors found: 218 studies (14170 participants) were included. Compared with active controls “usual care, placebo tablet, stretching, educational control, and social support,” large reductions in depression were found for: Compared with active controls, moderate reductions in depression were found for: Walking or jogging (n=1210, κ=51, g −0.63, −0.80 to −0.46) Yoga (n=1047, κ=33, g=−0.55, −0.73 to −0.36) Strength training (n=643, κ=22, g=−0.49, −0.69 to −0.29) Mixed aerobic exercises (n=1286, κ=51, g=−0.43, −0.61 to −0.25) Tai chi or qigong (n=343, κ=12, g=−0.42, −0.65 to −0.21)

Moderate, clinically meaningful effects were also present when exercise was combined with SSRIs (n=268, κ=11, g=−0.55, −0.86 to −0.23) or aerobic exercise was combined with psychotherapy (n=404, κ=15, g=−0.54, −0.76 to −0.32). All these treatments were significantly stronger than the standardized minimum clinically important difference compared with active control (g=−0.20), equating to an absolute g value of −1.16. For acceptability, the odds of participants dropping out of the study were lower for: Strength training (n=247, direct evidence κ=6, odds ratio 0.55, 95% credible interval 0.31 to 0.99) Yoga (n=264, κ=5, 0.57, 0.35 to 0.94)

Effects were moderate for cognitive behavior therapy alone (n=712, κ=20, g=−0.55, −0.75 to −0.37) and small for SSRIs (n=432, κ=16, g=−0.26, −0.50 to −0.01) compared with active controls.

Across modalities, a clear dose-response curve was observed for intensity of exercise prescribed.

Use of group exercise appeared to moderate the effects: Overall effects were similar for individual (g=−1.10, −1.57 to −0.64) and group exercise (g=−1.16, −1.61 to −0.73). Yoga was better delivered in groups. Strength training and mixed aerobic exercise were better delivered individually.

The authors concluded that exercise is an effective treatment for depression, with walking or jogging, yoga, and strength training more effective than other exercises, particularly when intense.

Comparing Antidepressants and Running Therapy on Mental and Physical Health Outcomes (Verhoeven et al., 2023)The objective of this study was to examine the effects of antidepressants versus running therapy on both mental and physical health. According to a partially randomized patient preference design (compares two or more interventions among groups of patients, some of whom choose the intervention they receive), 141 patients with depression and/or anxiety disorder (mean age 38.2 years; 58.2% female; 45 participants received antidepressant medication and 96 underwent running therapy) were randomized or offered preferred 16-week treatment: antidepressant medication (escitalopram or sertraline) or group-based running therapy ≥2 per week. Baseline (T0) and post-treatment assessment at week 16 (T16) included mental (diagnosis status and symptom severity) and physical health indicators (metabolic and immune indicators, heart rate (variability), weight, lung function, hand grip strength, fitness). The authors found: Intention-to-treat analyses (analyzing the results of RCTs that compares groups based on their initial treatment assignment, rather than the treatment they actually received) showed that remission rates at T16 were comparable (antidepressants: 44.8 %; running: 43.3 %; p=.881) There was a larger decrease in anxiety symptoms after six weeks in the antidepressant group, which suggests faster improvement on especially anxiety-related symptoms

However, the groups differed significantly on various changes in physical health: Weight (d=0.57; p=.001) Waist circumference (d=0.44; p=.011) Systolic (d=0.45; p=.011) and diastolic (d=0.53; p=.002) blood pressure Heart rate (d=0.36; p=.033) and heart rate variability (d=0.48; p=.006).

Adherence: In the antidepressant group, 82.2 % (N=37) of all participants adhered to the medication treatment protocol. In the running therapy group, 52.1 % (N=50) of participants completed >22 sessions of exercise therapy. The treatment adherence was significantly higher in the antidepressant group compared to the running therapy group (p<.001).

Limitation: A minority of the participants were willing to be randomized; the running therapy was larger due to greater preference for this intervention (out of 141 participants, 22 were willing to be randomized into the antidepressant [n=9] or the running therapy [n=13] groups, while 119 participants chose the treatment of their preference: antidepressant [n=36] or running therapy [n=83]). The authors conclude that while the interventions had comparable effects on mental health, running therapy outperformed antidepressants on physical health, due to both larger improvements in the running therapy group as well as larger deterioration in the antidepressant group.

Internet-Based Cognitive Behavioural Therapy Compared to Exercise for Depression (Hallgren et al., 2018)The objective of this RCT was to compare the effectiveness of exercise, internet-based cognitive behavioral therapy (ICBT), and usual care for depression. A multicentre, three-group parallel, randomized controlled trial was conducted with assessment at 3 months (post-treatment) and 12 months (primary end-point). 740 adults (mean age 43; 73% female; 56 received usual care, 49 received exercise, and 42 received ICBT) with mild to moderate depression aged 18–71 years were recruited from primary healthcare centres located throughout Sweden were included. Participants were randomly assigned to one of three 12-week interventions: Supervised group exercise: Patients in the exercise group were further randomized to one of three supervised exercise conditions: light exercise (yoga/stretching classes), moderate exercise (an intermediate aerobics class) and vigorous exercise (a higher-intensity aerobics/bodyweight strength training class). Patients were requested to complete three 60 min sessions per week for 12 weeks; sessions typically included 5–20 participants.

Clinician-supported ICBT: Usual care by a physician: Standard treatment for depression administered by their primary care physician. In most instances, ‘usual care’ consisted of 45–60 min CBT delivered by an accredited psychologist or counselor.

The authors found: Mean differences in MADRS score at 12 months were 12.1 (ICBT), 11.4 (exercise) and 9.7 (usual care) Exercise and ICBT had equivocal effects, which were greater than treatment as usual.

The authors conclude that the long-term treatment effects reported here suggest that prescribed exercise and clinician-supported ICBT should be considered for the treatment of mild to moderate depression in adults.

Exercise as an Add-On Therapy to Medications and CBT for Depression (Gourgouvelis et al., 2018) The objective of this study was to investigate the effects of exercise as an add-on therapy with antidepressant medication and cognitive behavioral group therapy (CBGT) on treatment outcomes in low-active MDD patients. Sixteen people were recruited; eight medicated patients performed an 8-week exercise intervention in addition to CBGT, and eight medicated patients attended the CBGT only. Twenty-two low-active, healthy participants with no history of mental health illness were also recruited to provide normal healthy values for comparison. The authors found: Exercise resulted in greater reduction in depression symptoms (p=0.007, d=2.06), with 75% of the patients showing either a therapeutic response or a complete remission of symptoms vs. 25% of those who did not exercise. Exercise was associated with greater improvements in sleep quality (p=0.046, d=1.28) and cognitive function (p=0.046, d=1.08).

The exercise group also had a significant increase in plasma brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF), p=0.003, d=6.46, that was associated with improvements in depression scores (p=0.002, R2=0.50) and sleep quality (p=0.011, R2=0.38).

The authors conclude that exercise as an add-on to conventional antidepressant therapies improved the efficacy of standard treatment interventions. Multisystem Benefits Of Exercise For Mental And Physical Health

Comorbidity Between Major Depressive Disorder and Physical Diseases (Berk et al., 2023)Those with common physical diseases (such as cardiovascular diseases, cancer and neurodegenerative disorders) experience significantly elevated rates of MDD, and those with MDD have an increased risk of numerous physical diseases. This significant comorbidity is associated with worse outcomes, reduced treatment adherence, increased mortality, and greater health care utilization/costs. The figure below demonstrates the association between MDD and various physical diseases according to Mendelian randomization studies. One issue we have with this study is that it suggests a unidirectional association between type 2 diabetes mellitus and major depressive disorder. However, other studies highlight the bidirectional relationship between major depressive disorder and both type 1 and type 2 diabetes. For instance, when blood glucose levels are well-controlled, depression scores tend to improve; conversely, when blood glucose levels are poorly controlled, depression screening scores often worsen. Similarly, as major depressive disorder symptoms improve, blood glucose levels also improve, and patients are more likely to adhere to blood glucose monitoring, insulin use, and dietary modifications. By contrast, an escalation in depressive symptoms correlates with a decline in these measures (Bernstein et al., 2013; Corathers et al., 2013; Massengale, 2005; Santos et al., 2015).

On top of the aforementioned physical health comorbidities associated with depression, antidepressant medications have several known side effects such as:

Therefore, although at best there is equivalence of efficacy between exercise interventions and medications or therapy, this does not mean these treatment modalities are all the same in the treatment of depression. Beyond its antidepressant effects, exercise has numerous multisystem benefits, which are often in contrast to the adverse side effects of antidepressant medications (Warburton et al., 2006). As such, exercise has the unique ability to simultaneously bolster one’s mental and physical health. Despite these beneficial multisystem effects and higher adverse events in antidepressant trials, there is a higher drop-out rate for exercise interventions (Recchia et al., 2022). This likely arises from the fact that exercise is physically demanding and more difficult to implement when compared to pharmacological interventions such as antidepressants. This places an onus of responsibility on the healthcare provider to develop an understanding of the benefits of exercise, address barriers, provide clear exercise “prescriptions,” and incorporate behavioral change techniques to increase initiation and adherence.

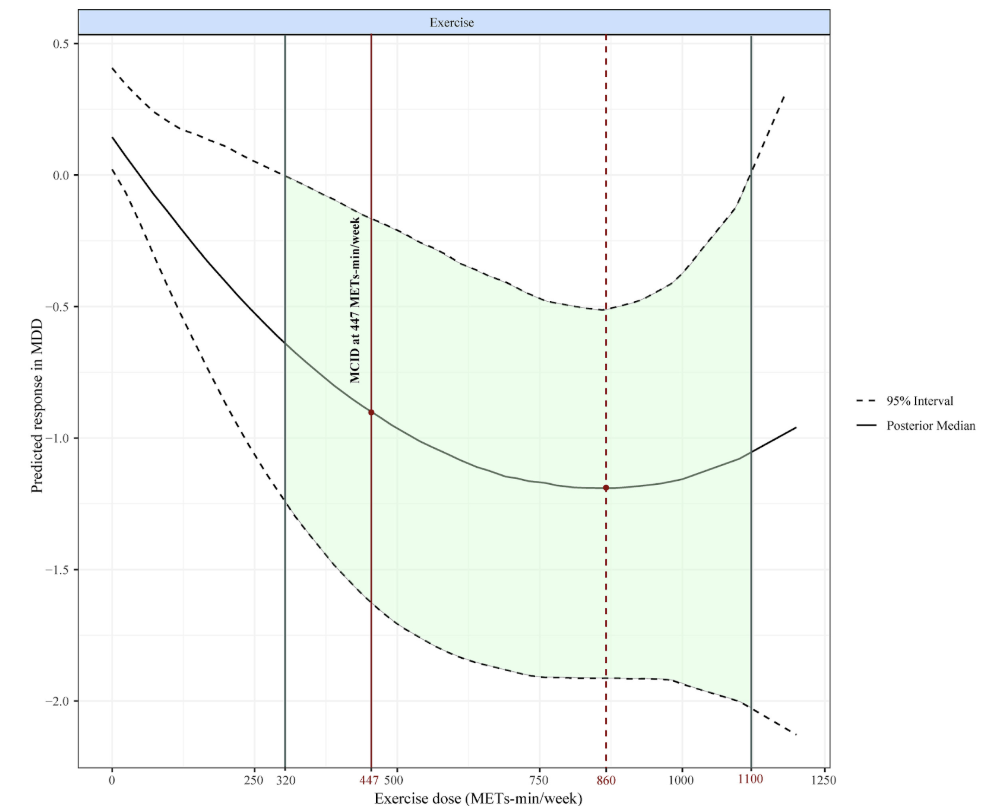

Optimal Amount of Exercise to Improve Depressive Symptoms (Tian et al., 2024)The objective of this systematic review and Bayesian model-based network meta-analysis of RCTs was to examine the efficacy of four major types of exercise (aerobic, resistance, mixed, and mind-body) on depression, as well as the dose-response relationship between total and specific exercise and depressive symptoms. People aged 18 years or older with a diagnosis of major depressive disorder, or a depressive symptom score above a threshold as determined by a validated screening measure, implemented one or more exercise therapy groups, and assessments of depressive symptoms at baseline and follow-up were included. The authors found: Forty-six RCTs (3164 people) were included. All exercise types improved depressive symptoms: Aerobic (SMD = -0.93; 95% CI: -1.25 to -0.62) Mind-body exercise (SMD) = -0.81; 95% CI: -1.19 to -0.42) Mixed (SMD = -0.77; 95% CI: -1.20 to -0.34) Resistance exercise (SMD = -0.76; 95% CI: -1.24 to -0.28)

The metabolic equivalent of task (MET) is a measure of the ratio of the rate at which a person expends energy, relative to the mass of that person, while performing some specific physical activity compared to a reference, currently set by convention at an absolute 3.5 mL of oxygen per kg per minute.

The dose-response meta-analysis showed a u-shaped curve between exercise dose and depressive symptoms.

Your browser does not support the audio element.

Your browser does not support the audio element.

|

More

More

Religion & Spirituality

Religion & Spirituality Education

Education Arts and Design

Arts and Design Health

Health Fashion & Beauty

Fashion & Beauty Government & Organizations

Government & Organizations Kids & family

Kids & family Music

Music News & Politics

News & Politics Science & Medicine

Science & Medicine Society & Culture

Society & Culture Sports & Recreation

Sports & Recreation TV & Film

TV & Film Technology

Technology Philosophy

Philosophy Storytelling

Storytelling Horror and Paranomal

Horror and Paranomal True Crime

True Crime Leisure

Leisure Travel

Travel Fiction

Fiction Crypto

Crypto Marketing

Marketing History

History

.png)

Comedy

Comedy Arts

Arts Games & Hobbies

Games & Hobbies Business

Business Motivation

Motivation