|

Description:

|

|

Joanie Burns, DNP, APRN, PMHNP-BC; Adam Borecky, MD; David Puder, MD

“Between stimulus and response there is a space. In that space is our power to choose our response. In our response lies our growth and our freedom.”

— Viktor Frankl

IntroductionThe 5-factor approach to holistic, patient-centered psychiatric care takes into account that each individual who seeks care is unique in their physiological and psychological make-up and that there are multiple factors that influence both physical and mental health (for better or worse). While the serotonin theory and other neurochemical theories (aka “chemical imbalance” theories) continue to dominate pop-culture understandings of psychiatry, there is growing evidence that there are multiple causative factors for depression and other mental health diagnoses. Therefore, it is helpful to understand that various factors may be contributing to the presenting symptom(s) and to offer a multi-faceted approach that addresses these factors and alleviates the symptoms.

The 5-factor approach addresses four environmental factors (therapy, sleep, activity, and nutrition) that patients and their caregivers may choose to modify in order to improve overall well-being, as well as the option of including medication/s (the 5th factor). While therapy may not be considered a typical “environmental” factor, in some respects, as with modifying sleep, activity, and nutrition, a patient chooses to attend and participate in therapy and to implement the skills learned in therapy. Likewise, although to a lesser degree, the utilization of medications may be considered a pseudo-environmental factor in that patients make a conscientious/thoughtful choice to accept a medication option, fill the prescription, and take the prescription as directed. At times, this may include modifying or creating a schedule to maintain consistency with a medication regimen and, possibly, the addition of other activities to maintain or improve medication compliance, such as establishing a designated time each week to fill a pill sorter/organizer.

The 5-factor approach to treatment is based on the importance of sensorium and its pivotal role in regulating thoughts, feelings, and overall mental health. Sensorium is a lens to understand how we focus on various things. Sensorium is total brain function, which fluctuates throughout the day and depends on a number of factors, including sleep, stress levels, and more (Ep. 6; Ep. 9; Ep. 10; Ep. 11; Ep. 85; McLaughlin et al., 2007). The 5 FactorsTherapy Sleep Activity Nutrition Medication/s

PsychotherapyGiven the heavy emphasis on psychopharmacologic/psychotropic interventions due to chemical imbalance theories, the benefits of psychotherapy and supportive therapeutic interactions are often downplayed or overlooked (Ahmad, 2023; Moncrieff et al., 2022). Additionally, many patients are under the impression that medications are a “quick fix.” Of note, the rate of prescribing medication increased dramatically during the COVID pandemic (Sanborn et al., 2023), and while the percentages of patients receiving any mental health treatment (including therapy) have also increased (Hasin & Grant, 2015; Terlizzi & Schiller, 2022), the prescribing of psychotropic medications remains the default treatment of choice for both providers and patients alike. There is a cultural factor as well, as Americans [in particular] may have “a large appetite for pharmacological treatments” (Kukreja et al., 2013), which may or may not be appropriate (Ep. 157). Simply put, too many patients are being prescribed medication without adjunctive psychotherapy or lifestyle changes (Mojtabai & Olfson, 2008). Because of these factors, mental health concerns are not being treated in the most effective way possible. This is especially the case when considering the treatment of psychological trauma, for which talk therapy can cure in ways medications cannot (Ep. 19; Fischer et al., 2022).

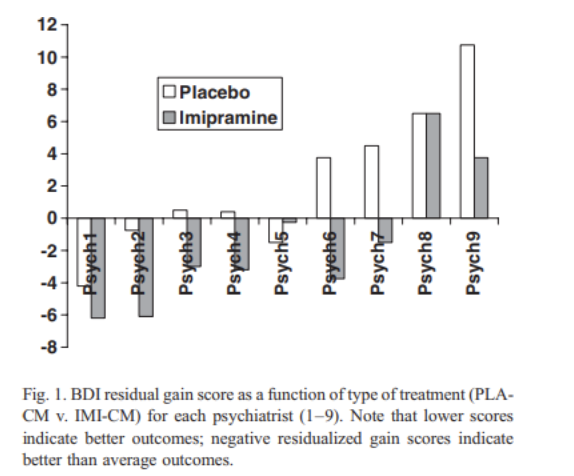

While there is evidence pointing to an increase in referrals for psychotherapy, in comparison to data regarding psychotropic prescribing, a wide discrepancy between referrals for these treatment modalities still exists. Notably, McKay and colleagues (2006) highlight how referrals for medication are numerous despite evidence that the “psychiatrist effect” shows more is happening in psychiatry than just medications (Ep. 168):

The proportion of variability in outcomes was due less to the treatment received than to the psychiatrist administering the treatment. The person of the psychiatrist makes a difference in the response to antidepressant medication. The health care community would be wise to consider the psychiatrist not only as a provider of treatment, but also as a means of treatment (McKay et al., 2006).

In one study on obsessive compulsive disorder (OCD), two groups of people were studied—those who underwent cognitive behavioral therapy, and those that took medication. The therapy was found to be as helpful in eliminating OCD symptoms. However, the OCD symptoms returned when the medication was stopped. The symptoms did not return when the person had received cognitive behavioral therapy (Baxter, et al., 1992; Ep. 19).

(McKay et al., 2006)

The positive influence of supportive therapeutic interactions is very apparent in the data from meta-analyses showing significant improvement/resolution of symptoms in patients receiving a placebo during medication trials. “Physicians' failure to establish good rapport with patients accounts for much of the ineffectiveness of care” (McKay et al., 2006). Further supporting the efficacy of therapy as an intervention is the recommendation for therapy (with or without psychotropic medication) in resources such as A Guide to Treatments That Work (Nathan & Gorman, 2015), Psychopharmacology Algorithms (Osser, 2021), Kaplan and Sadock's Synopsis of Psychiatry (Sadock et al., 2015), Psychopharmacology and Pregnancy (Galbally et al., 2014), and the recommendations developed by the United States Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) (Cheung et al., 2018; Siu & USPSTF, 2016; Siu et al., 2016), to name a few.

What do our patients gain from incorporating therapy into their treatment regimen?

Therapeutic interventions provide long-lasting change. More robust than medication interventions for abating and resolving symptoms long term. Expand support system/wellness team.

Is a specific therapeutic modality recommended?Several studies have shown that the therapeutic relationship (rapport between patient and provider) has more bearing on symptom improvement than the modality of therapy employed (Ankarberg & Falkenström, 2008; Ep. 171; McKay et al., 2006; Wampold & Imel, 2015). In an article published in 2010, Dr. Shedler (Ep. 144) expands on this dynamic and highlights how the therapeutic relationship also impacts medication compliance and response to psychotropic medications. To further define and quantify the aspects of therapeutic rapport, Dr. Puder developed a metric called the Connection Index (CI) (Ep. 149; Puder et al., 2022). Utilizing the CI, he has shown how higher scores correlate with better outcomes in supervision (Ep. 149; Puder et al., 2022); other, similar studies have shown this for therapy (more immediate and long-term improvement).

A highly effective therapeutic modality called mentalization-based therapy (MBT) is discussed in “Psychiatry & Psychotherapy Podcast” ep. 205, where doctors Puder, Bateman, and Fonagy highlight the efficacy of MBT and long-duration therapy (Bateman & Fonagy, 2008; Bateman & Fonagy, 2013). Specifically, MBT has demonstrated significant potential to reduce the symptoms, distress, and severity of comorbidities, while increasing the quality of life and relationships in patients with borderline personality disorder (BPD) (Vogt & Norman, 2019).

Signs therapy is working:

Increased connection with others (Ep. 205; McWilliams, 2004) Nancy McWilliams: the overall aspects of mental health include (Ep.171): Sense of safety and trust in oneself, others, and the world Sense of Agency Sense of continuity Self-esteem Affect tolerance Self-preservation and Altruism Acceptance Capacity to love, work, and play

Free will/self-regulation (the idea of self-efficacy improving and all the positive associated outcomes) (Baumeister, Crescioni, & Alquist, 2011; Ep. 84, Ep. 85, Ep. 86) Increased vulnerability with the therapist (Ep. 205)

How Long Does Effective Therapy Take?Dr. Shedler and co-author, psychologist Eric Gnaulati (2020), have also written on the question of how much time is needed for therapy to produce meaningful change. In this article, “The Tyranny of Time: How Long Does Effective Therapy Really Take?,” they present evidence that effective therapy takes significantly longer than the 8- to 16-week treatments often used in controlled trials (Ep. 144) (see also Bateman & Fonagy, 2008; Bateman & Fonagy, 2013; Ep. 205; Verheul et al., 2003).

Because of the incredibly difficult nature of studying psychotherapy, researchers typically chose shorter periods of time, 8- and 16-week trials, to study, but not on the basis of research that shows these are inherently beneficial time frames to begin with. Consequently, there are hundreds of studies on treating depression alone, all based on treatments of <16 sessions. A recent large meta-analysis showed that CBT was effective at getting 20% of people into remission compared to wait list control. The reason it was only 20% is because the studies were short! The insurance companies would love for 12 sessions to be idealized as the “gold standard,” however, in clinical practice this is not enough to get the other 70-80% into remission!

A study of over 10,000 therapy clients, assessed session-to-session with a validated outcome instrument, found that it took 21 sessions or about six months of weekly therapy to see clinically significant changes in 50% of patients. Only after 40 sessions, or almost a year of weekly therapy, did researchers see significant changes in 75% of patients (Lambert et al., 2001). Research has also called into question the long-term efficacy of brief therapy (Shedler & Gnaulati, 2020). Yet brief manualized therapies are still frequently viewed as the standard of care, and most research on psychotherapy continues to focus on abbreviated therapy. Multiple factors explain the continued predominance of brief therapy. One issue is a lack of communication between researchers and clinicians. Few studies have asked practicing therapists how long it takes for therapy to show significant effects, and when the question is asked, they find that practitioners generally see better results with long-term therapy. An Emory University survey of 270 experienced psychotherapists found that their last completed therapies “in which patient and therapist agreed that the outcome was reasonably successful” required a median of 52 to 75 sessions (Morrison et al., 2003).

Compared to brief therapy, long-term therapy is also simply less studied. Practical constraints are partly to blame: studies of long-term therapy are expensive, methodologically complex, and resource-intensive. But the relative lack of research on long-term therapy also creates a self-fulfilling prophecy: when “less-studied” is falsely equated to “less evidence-based”, it perpetuates the stereotype that long-form therapy is not evidence-based.

Dr. Shedler concludes that “real therapists operating in the real world recognize that therapy takes time and that people don’t come packaged with single DSM disorder categories. People are complex and there is a need to create a relationship with the patient over time. The actual schism is between practicing clinicians and researchers who operate in cognitive parallel universes” (Ep. 144).

The efficacy of therapy as an essential component of treatment is further exemplified by a study conducted by doctors Fonagy and Bateman (2008) that followed patients diagnosed with borderline personality disorder (BPD) 5 years after receiving 18 months of individual and group mentalization-based therapy through a partial hospitalization program and an additional 18 months of twice-weekly mentalization based group therapy. The study yielded statistically significant reductions in suicide attempts, emergency room utilization, quantity and duration of psychoactive medications, and the presence of symptoms that qualify for a diagnosis of BPD. Of specific interest, the treatment group, had a mean of 0.02 years of the 5 years of follow up on 3 or more drugs, where the treatment as usual had 1.9 years on 3 or more drugs, illustrating the impact of enough therapy on long-term outcomes with decreased need of medications.

One group of patients underwent either 18 months of intensive partial hospitalization mentalization-based treatment, at approximately 9 hours of therapy per week for a total of 648 treatment hours, while the other group underwent treatment as usual for BPD. The MBT group then continued with less intensive MBT groups twice a week for an additional 18 months (144 more treatment hours). The standard treatment group did not have any interventions after the initial 18 months. Then, both groups were followed for an additional 5 years without any further interventions. Significant differences were found at the 18-month check-in, 36-month check-in, and the final 8 year check-in. Differences in the MBT vs. standard treatment groups were increased over the 5 year periods for each outcome (Bateman & Fonagy, 2008; Ep. 206).

Studies Show Psychotherapy Changes The BrainAll interventions that work to cure depression have a “final common pathway” of leading to positive brain changes via neuroplasticity changes, a marker of which is brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) and other neurotrophic factors.

A PTSD study by Fischer, Schumacher, and Daniels (2022): “PTSD is characterized by specific neurobiological alterations, with preliminary findings indicating that at least some of these may normalize during psychotherapy.”

SleepPhysical and cognitive/emotional functions rely on adequate sleep (Ep. 11). Therefore, regulating sleep helps modulate mood and physical wellbeing and is one of the few things that is easily modified and customized to fit our individual needs. Sleep is an essential component of mental health, so much so that changes in sleep are part of diagnostic criteria for depressive disorders, anxiety disorders, and many other psychiatric disorders (American Psychiatric Association; Ep. 65). Current studies have highlighted an alarming increase in reports of depression, anxiety, and suicidal ideation by persons of all ages, while recent studies regarding sleep are yielding data that point to an increasing trend of sleep deficit, which correlates with worsening physical and mental health.

Recommendations from the CDC and Sleep Foundation:

9-12 hours recommended for school-age children (6-12yo) 8-10 hours recommended for teens (13-18yo) Significant phase for brain growth, development and connectivity R/L brain connections finalizing (generally complete between ages 17-21yo)

7+ hours recommended for adults (CDC, 2022; Suni, 2022).

A dialogue about sleep:

What is your current sleep schedule? What time do you go to bed? How long does it take you to fall asleep? Do you wake up during the night? If so, how often and are you able to fall back to sleep? What time do you typically wake up for the day? Do you feel refreshed when you wake? Caffeine intake? Exercise/activity before bed? Sleep apnea (or other respiratory concerns)? Medications or other substances that may impact sleep?

For problematic sleep:

(Hartley et al., 2022)

How To Change Sleep HabitsProvide patients with sleep hygiene tips (preferably in writing). There are open source tip sheets available online. One such resource is provided by the CDC: Tips for Better Sleep | CDC. Often, if referring to a sleep specialist, patients will be asked the above questions and be advised to implement improved sleep hygiene practices with or without the aid of medications. For some patients, in the absence of a sleep wake disorder, sleep apnea, or other physiological problem causing sleep disruption, refining sleep habits (implementing some/most of the sleep tips) is a cost-effective and efficacious means to achieve consistent sleep on most nights. ActivityExercise has been found to have better compliance and less side effects when compared to pharmacological interventions, and may be used as a beneficial adjunct to traditional pharmacological methods (Ep. 8; Pajonk et al., 2010; Ströhle et al., 2015).

How does activity improve mood?

“Feel good” chemicals such as endorphins and dopamine are released during activity/exercise. There are other lesser known, but no less impactful, chemicals released during exercise (Hunsberger et al., 2009; Turner et al., 2020). Physical and emotional strength/resilience increase (Blumenthal et al., 2007). Increased exposure to eustress (ex: gradual increase of weight training) over time increases overall physical and psychological resilience (Mucke et al., 2018). Low muscle mass with poor mitochondrial health is associated with cognitive impairment. When mitochondria function is increased, there is potentially a higher capacity to weather stressors on a cellular level (Oudbier et al., 2022). Improved sleep.

Thinking back to therapy fundamentals with the cognitive triangle and “feelings follow actions/behavior,” the goal would be to support patients in developing their own plan to implement positive/healthy activity(ies) that will promote wellness. This may mean helping a patient rewrite their internal negative script of “I can’t” or “It’s too hard” to “I can” or “I did it.” We like to use the analogy of baby steps and we remind patients that we are not asking/demanding CrossFit Extreme (for example), but one step toward the patient’s goal(s). Just as we get excited over the baby steps of a toddler, we can share that excitement for ourselves and with each other about the baby steps of growth/personal development we are experiencing from our applied efforts. Too often, we hear people discredit their work. In these instances, we strive to highlight the accomplishment and help the patient acknowledge what they have achieved and give themselves permission to take credit for their work. An example: “I only walked 5 minutes today” reframed as, “I walked 5 minutes today!”

There is evidence to support the efficacy of weight/strength training for improved mental health (Blumenthal et al., 2007; Ep. 10; Ep. 18; Ep. 96; Ep. 142; Ep. 165; Mucke et al., 2018). Again, this is not intended to imply that extreme activity/training is needed to achieve improvement. Taken in its purest sense, this is the gradual increase of strength exercises over time, building both physical and psychological resilience. NutritionNutrition also plays a role in mental health (Ep. 9, Ep. 59, Ep. 131; Jacka et al., 2017; Lane et al., 2022; Sánchez-Villegas et al., 2009). Of the 5 factors, this is the area that we typically receive the most pushback, often in the form of questions like: “What does food have anything to do with how I feel?” Simply put, what we eat matters, not only for physical well-being, but also for cognitive-emotional health. Take into consideration the proportion of the brain to the overall size of the body. This relatively small part of your body utilizes one-quarter of your daily caloric intake! Choosing healthy meal options equates to choosing clean (cleaner) fuel for the brain. Additionally, when we choose to eat (refuel) makes a difference, as well. Think about how we feel/act when we are hungry – not our best selves (“hangry” is a real thing) (Ep. 9).

Similar to the activity factor, the expectation is not for extreme or fad dieting. The goal is for well-rounded meals with appropriate proportions of micro and macro nutrients and making small, incremental changes versus an overnight dietary overhaul (remember…baby steps).

When is food going to give the biggest win?

Getting rid of unhealthy foods (ultra-processed foods), adding healthy foods, and learning to eat them mindfully made a significant difference in depression symptoms (Ep. 131; Ep. 187; Jacka et al., 2017; Lane et al., 2022). A study of 10,094 participants found that diet impacted how many future depressive events took place (Ep. 131; Sánchez-Villegas et al., 2009). Diet can potentially prevent future episodes of depression, with a particular value of increased fruits, nuts, high monounsaturated fatty acids (MUFAs) foods, and fish in moderation (Ep. 131; Sánchez-Villegas et al., 2009).

There are specific vitamins and minerals that are known to impact mental health (Ep. 59) when a deficiency is present. For example, low vitamin D (Lerner et al., 2018) and low folate (vitamin B-9) (Martone, 2018) are associated with depression, and low iron often causes fatigue, which mimics the anergia of depression.

Lack of omega-3 in the diet has been associated with depression and anxiety, according to research into the inflammatory processes that contribute to sub-optimum mental health (Ep. 131; Dighriri et al., 2022; Wenk, 2022). Additionally, adequate omega-3 has been attributed to reduced symptomatology of anxiety, attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), autism spectrum disorder (ASD), depression, and schizophrenia (Lange, 2020).

Getting omega-3 through whole foods (Cleveland Clinic, 2023; Dighriri et al., 2022) is important: chia seed, flax seed, salmon, walnuts, spinach, brussel sprouts, seaweed.

Cleveland Clinic, 2023

(Cleveland Clinic, 2023)

When considering/assessing dietary deficiencies, it may be helpful to obtain lab work or collaborate with the patient’s primary care provider (PCP), as in some cases, prescription repletion is needed versus relying on over-the-counter (OTC)-strength supplements. A Role For MedicationThere is a lot that can be said here, but the overarching concept, regardless of medication, is maintaining an open dialogue to foster a patient-centered team approach to care. This often entails acknowledging, by saying out loud, “I understand the medications, but you are the expert on you and your input is important,” as well as considering what the research/literature recommends and balancing this with how the patient feels about medication(s). One way to approach this is to emphasize that the recommendations are options, not mandates. This may be especially helpful for a patient who needs to feel that they have control over the process/autonomy over their person. With this in mind, the provider and patient work together to find the best fit for the patient: what will target symptoms, has the lowest side effect potential, and works with the patient's lifestyle/needs.

From a conservative approach, initiate medications “low and slow” and titrate to the lowest effective dose. While there are prescriptions available for just about everything, the goal is to utilize the least amount of medication possible (Ep. 19) and help to make this attainable by implementing any, or all, of the first 4 factors.

Alternatively, in a crisis situation there is a role for putting the fire out—making immediate and frequent changes to rapidly optimize medication efficacy and assist someone out of a very acute episode.

In Episode 19, Dr. Cummings uses a simple guideline to see if someone would benefit from medicine or talk therapy:

If what the person is depressed about is something in their lifestyle—their weight, job, relationship—lifestyle changes and talk therapy will probably be most effective. If someone is experiencing neurovegetative symptoms of depression, such as: loss of appetite or increased appetite, severe energy loss, severe sleep disturbance with early morning awakening, physically slowed down, they are suffering from brain disturbances that are helped by medication.

Is Medication Forever?

Often, we are asked by patients if medication is forever. This may be one of the most difficult conversations to have with patients, as many patients do not want to hear that long term, or lifelong medication is needed and recommended. It may be helpful to approach the dialogue from a symptomology and/or diagnosis standpoint: “The experts have studied this thoroughly and find that people who have similar symptoms to what you are experiencing will need ____.” For example: single depressive episode = 4-9 months following stabilization according to the APA’s Clinical Practice Guideline for the Treatment of Depression Across Three Age Cohorts (2017), while other sources recommend longer duration of psychotropic medication following point of remission (Shelton, 2001; Zwiebel & Viguera., 2022); recurrent anxiety or depression (specifically, 3+ episodes) = lifelong medication (Miller, 2013); obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD), bipolar disorder, schizophrenia = lifelong medication (Ep. 19; Gitlin et al., 2001; Robinson et al., 1999). While it is preferable that patients hear us out and want to follow recommendations in order to avoid decompensation and maintain progress toward their goals, it is helpful to maintain a supportive and empathic “options, not mandates” approach, employing motivational interviewing (MI) (Ep. 199; Miller & Rollnick, 2023; Shea, 2017) and sharing resources from the Common Ground Program (Deegan, 2023) to support patient autonomy and their treatment goals. Neuroleptic Discontinuation Study (Ep. 8): Exacerbation or relapse was almost universal within 2 years in those who discontinued antipsychotics (Gitlin et al., 2001). “Consistent evidence shows that neuroleptics, administered as a maintenance treatment, reduce relapse rates in schizophrenic patients. A comprehensive review that analyzed 66 studies found a mean cumulative relapse rate of 53% in patients withdrawn from neuroleptic therapy compared to 16% for those maintained on a regimen of neuroleptic therapy” (Gitlin et al., 2001). “Robinson et al. (1999) found that patients who discontinued antipsychotic medications (not randomly assigned but self-selected) following at least 1 year of treatment relapsed at a rate almost five times that of those who continued taking medications over a 5-year period” (Gitlin et al., 2001).

PolypharmacyThere are times when patients are on numerous medications. Whether polypharmacy occurs intentionally or unintentionally, it is important to attempt a thorough medication reconciliation during each appointment and to eliminate redundancies, medication overlap, and medications that complicate/hinder the wellness process (Ep. 19; Ep. 157). “Pill burden” and side effects are often-cited reasons for discontinuing medications. Therefore, striving to utilize the lowest effective dose of the fewest medications is an important aspect not only from a physiological standpoint but also for improving long term medication compliance. Read et al. (2017): Polypharmacy increased, and in some cases doubled, the risk of adverse effects. The total number of psychotropics was correlated with progressive risk of adverse effects, and was inversely correlated to perceived efficacy of the drugs (Ep. 157).

(Read et al., 2017)

There are several types of polypharmacy. Read et al.’s (2017) definition of polypharmacy, several drugs in multiple classes, is a common one. Further elaborating on polypharmacy, Kukreja et al. (2013) explain there are other ways to define the issue. Polypharmacy can refer to redundancy with multiple drugs in the same class. Adjuvant polypharmacy refers to the use of one drug to treat the adverse effects of another. Polypharmacy through augmentation occurs when one drug’s dose is maximized, but symptoms remain. In these cases, another agent is added to continue to pursue a treatment effect. Additionally there is total polypharmacy, the absolute number of medications regardless of class, mechanism, and indication (

Your browser does not support the audio element.

|

More

More

Religion & Spirituality

Religion & Spirituality Education

Education Arts and Design

Arts and Design Health

Health Fashion & Beauty

Fashion & Beauty Government & Organizations

Government & Organizations Kids & family

Kids & family Music

Music News & Politics

News & Politics Science & Medicine

Science & Medicine Society & Culture

Society & Culture Sports & Recreation

Sports & Recreation TV & Film

TV & Film Technology

Technology Philosophy

Philosophy Storytelling

Storytelling Horror and Paranomal

Horror and Paranomal True Crime

True Crime Leisure

Leisure Travel

Travel Fiction

Fiction Crypto

Crypto Marketing

Marketing History

History

.png)

Comedy

Comedy Arts

Arts Games & Hobbies

Games & Hobbies Business

Business Motivation

Motivation